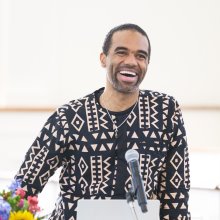

On Friday, September 5, the artist and engineer Mikael Owunna ’08 returned to the stage of Western Reserve Academy’s Chapel. Rows of students in familiar green blazers sat upright in the pews, with that familiar mix of curiosity and quiet conversation, before Owunna — an alumnus once in their place — stepped to the podium. For him, the moment was a double homecoming. He had been back in May, premiering work in the Moos Gallery during Reunion Weekend. Now he was here, summoned to speak again, this time to students.

Owunna’s resume could fill several pages. A graduate of Duke with degrees in biomedical engineering and history, he went on to Oxford as a Rothermere Scholar and to Taiwan on a Fulbright. He is the co-founder of Rainbow Serpent, an art-tech-spirituality collective, and the current president of Pittsburgh’s Public Art and Civic Design Commission, where he has helped reimagine the city’s skyline — among many projects, he lit the Three Sisters bridges, seen by more than two million people. His media spans the contemporary spectrum: photography, VR, AR, blockchain, performance, zero gravity. In January, his work will hang in the Smithsonian. Recently, Time named him one of its “national cultural leaders.”

His introduction, delivered by Fine & Performing Arts Department faculty Midge Karam ’79 emphasized not just his credentials, but his transformation: “He began as a math-and-science guy,” she said, “and became an artist.”

That journey, Owunna reminded the audience, was not seamless. At Reserve, Mikael had drafted his senior “This I Believe” speech years in advance, intending to write about coming out. By the time his turn arrived, he gave a different talk entirely, one that masked himself rather than revealed him. “It wasn’t representative of me,” he told students. “It was representative of my fear.”

The Chapel was hushed. The story carried the weight of memory, of a campus in 2008 that offered fewer protections, fewer communities for marginalized students, fewer open doors for a queer Nigerian teenager. Owunna described the exorcisms his family subjected him to in Nigeria, the long depression that followed and the tentative turn toward healing when a friend at Duke said, “I think we should bring cameras with us to Oxford.”

From there, Owunna’s artistic vision coalesced into something both cosmic and personal. Take his Infinite Essence series, which depicts Black bodies painted in fluorescent pigments and photographed in total darkness captured in an ultraviolet flash. The effect is startling: the figures appear as radiant constellations, celestial beings in the universe, scenes inspired by the archive of African diasporic myth.

It’s engineering that makes this magic possible. Owunna built his own camera flash to reveal what the human eye cannot see — but the meaning is metaphysical. “Photography comes from the Greek: phos, graphē, to draw with light,” Owunna explained. “Here, I am drawing with blackness, with an invisible spectrum, to show the Black body as a cosmic entity.” Further, Owunna reimagines the visual language around Blackness, countering its frequent association with violence and death. Instead, his images render Black bodies as radiant and life-giving, brilliantly illuminated as opposed to shadowed, celebrated rather than silenced.

Darkness, in Owunna’s work, is not absence but presence: fertile, generative, imaginative, cosmic. It is a question posed to the themes of Western art that explore brightness, whiteness, light. It is also an act of recovery. When family members told him it was un-African to be queer, Owunna sought proof to the contrary, and he found it in precolonial primary and secondary sources: deities and gatekeepers who embodied androgyny, communities that embraced gender as energy rather than anatomy. His research, as much as his art, dismantles erasure.

Owunna’s Chapel talk, titled Essence of En-Darkenment: A Homecoming, braided these strands together — identity, mythology, technology, survival. Following his talk, on Monday during Morning Meeting, Alice Yu ’28 stood at the same podium, announcing that she would be offering “Free Hugs” at lunch, an act of solidarity that may or may not have been inspired directly by his visit but felt, to those who witnessed both, like a response.

The applause at the end of Owunna’s talk was long and loud, with students rising eagerly to their feet for a standing ovation. Hands raised with questions about his journey, his process, his advice. Later, he lunched with the DEIB student committee and visited a Compass class (at students’ eager insistence). When he finally departed, he left behind not just the glowing photographs in Moos Gallery but a sense of changed air: that homecomings can heal, that art can expand the cosmos, that the Chapel’s stage can become a site of reclamation.

.jpeg&command_2=resize&height_2=85)